Find out what happens when the team discovers that there is apparently no more diesel in Tashkent and how they managed to scrounge up enough to get to Samarkand, a beautiful city filled with amazing architecture and Islamic history.

Find out what happens when the team discovers that there is apparently no more diesel in Tashkent and how they managed to scrounge up enough to get to Samarkand, a beautiful city filled with amazing architecture and Islamic history.Steve Dew-Jones:

There appears to be a distinct lack of Diesel in this part of the world – so much so that it almost put paid to any hopes we had of leaving Tashkent yesterday. We must have tried half a dozen petrol stations on our way out of the city yesterday morning and at each we found the same response. The attendant’s arms would be crossed to show that no Diesel was present and we would be pointed towards the next one, “One kilometre” up the road.

Having tried several “next ones” already, each without success, and given that our petrol gauge was once again dropping drastically low, it wasn’t long before we ignored this advice and spun around back to the capital. Surely the city centre of Uzbekistan’s biggest city would be our most likely source of fuel.

“So what next?” the five of us (Amanda and Jamie have arrived in Jo’s stead) mused, as we enjoyed a surprise return to the restaurant at Hotel Malika.

There didn’t seem much that we could do - it really did seem that we were fighting a losing battle – but as a last resort, a taxi was hailed and Bryn and I were to be driven around, jerry can in hands, for as long as it took before we stumbled upon that elusive Diesel pump.

And so off we went, and picked up where we left off, stopping at the very same petrol stations upon the very same road that we’d already driven along twice.

“No!” I protested to the driver. “Diesel nada.” But our bemused friend knew best. Pulling over beside the fifth petrol station to confer with a group of truckers, we were pointed down a little alleyway, where we soon arrived to the joyous sight of one particular trucker siphoning some Diesel from his tank into the jerry cans of another group of frustrated drivers – presumably for a princely sum.

Well, the price mattered little by that stage, and Bryn and I soon bought 45 litres’ worth (and eventually went back again for an extra 20), before heading back to the hotel to fill up the tank and set off to Samarqand – home to some of the most impressive Muslim architecture that I have ever seen.

Quite what we’ll do about the Diesel shortage in a few days’ time, I do not know. Perhaps Samarqand will be different, but that seems unlikely, given that there was none in the capital. For the moment, we will just sit back, relax, and enjoy our new surroundings in the enchanted city of Samarqand.

Sophie Ibbotson:

In my mind, Samarkand and Kashgar are the two great Silk Road cities. I went to Kashgar in 2008 and was sorely disappointed by the way the Chinese had flattened the city, consciously burying thousands of years of world history under strip malls, neon signs and mile after mile of concrete. It was therefore with some trepidation that I approached Samarkhand, not knowing if UNESCO had been able to hold back the ravages of time, cultural imperialism, and a chronic lack of taste.

The outskirts of Samarkand are not too promising. I bit my lip and kept my fingers crossed. As we came around the ring road, skirting fairly characterless blocks of flats and administrative buildings, the Registan popped into view across the rooftops. I let out a sigh of relief.

The origins of Samarkhand date back some 3000 years, but the most ancient parts were destroyed by Genghis Khan. The buildings we see today were built by his descendants between the 14th and 17th centuries AD. The so-called Timurid dynasty ruled an empire that stretched from Ankara to Delhi. Samarkand was their capital and, as such, a centre of patronage that drew the finest architects and artisans of the day. The superior quality of their work is clear in every dome, tile and tower.

years, but the most ancient parts were destroyed by Genghis Khan. The buildings we see today were built by his descendants between the 14th and 17th centuries AD. The so-called Timurid dynasty ruled an empire that stretched from Ankara to Delhi. Samarkand was their capital and, as such, a centre of patronage that drew the finest architects and artisans of the day. The superior quality of their work is clear in every dome, tile and tower.

We stayed in a guesthouse a stone’s throw away from the Guri Amir mausoleum (the tomb of Amir Timur, sometimes known as Tamerlaine). The house was built in a traditional style around a courtyard, with fruit trees to offer shade. From the bedroom door we could reach out and pluck fat, juicy cherries to eat. At breakfast, served at a communal table in a second white-washed courtyard, we devoured fresh bread, homemade mulberry and rose petal jams, pastries, potato cakes and crepes. It was a perfect start to each day.

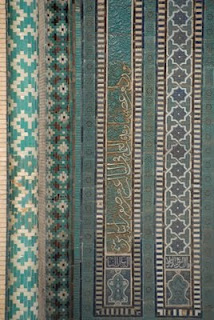

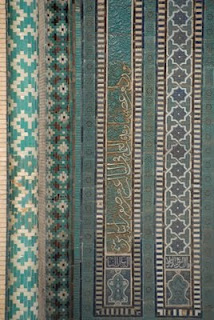

Quite understandably, it is the Registan that attracts the most attention in Samarkand. This exquisite collection of mosques and madrassas (Islamic schools) is arranged dramatically on three sides of a square, with the archways of the principal buildings rising up imposingly. Although the buildings themselves are brick-built, every inch of their facades are richly tiled. The majority of the tile work features the geometric patterns typical on Islamic buildings, but there is one notable exception: there are two orange tigers staring down at you from the corner panels of the archway to the right.

My favourite discovery, however, is far less frequented. On the furthest edge of the city’s graveyard, having disturbed a few sleepy marmots and an occasional snake, we discovered a row of domed tombs, the earliest of which dates from the 1300s. The place is quiet – there wasn’t another tourist in sight – and so, as we walked, it felt timeless. The tiles were a combination of a deep royal blue and shades of turquoise, all with an immaculate sheen that caught the evening light. A solitary figure, possibly an Imam, appeared briefly, paused to look along the length of the paved avenue between the tombs, and then disappeared as suddenly as he had come. The last of the day’s light faded and we wandered home entranced.

My favourite discovery, however, is far less frequented. On the furthest edge of the city’s graveyard, having disturbed a few sleepy marmots and an occasional snake, we discovered a row of domed tombs, the earliest of which dates from the 1300s. The place is quiet – there wasn’t another tourist in sight – and so, as we walked, it felt timeless. The tiles were a combination of a deep royal blue and shades of turquoise, all with an immaculate sheen that caught the evening light. A solitary figure, possibly an Imam, appeared briefly, paused to look along the length of the paved avenue between the tombs, and then disappeared as suddenly as he had come. The last of the day’s light faded and we wandered home entranced.

There appears to be a distinct lack of Diesel in this part of the world – so much so that it almost put paid to any hopes we had of leaving Tashkent yesterday. We must have tried half a dozen petrol stations on our way out of the city yesterday morning and at each we found the same response. The attendant’s arms would be crossed to show that no Diesel was present and we would be pointed towards the next one, “One kilometre” up the road.

Having tried several “next ones” already, each without success, and given that our petrol gauge was once again dropping drastically low, it wasn’t long before we ignored this advice and spun around back to the capital. Surely the city centre of Uzbekistan’s biggest city would be our most likely source of fuel.

“So what next?” the five of us (Amanda and Jamie have arrived in Jo’s stead) mused, as we enjoyed a surprise return to the restaurant at Hotel Malika.

There didn’t seem much that we could do - it really did seem that we were fighting a losing battle – but as a last resort, a taxi was hailed and Bryn and I were to be driven around, jerry can in hands, for as long as it took before we stumbled upon that elusive Diesel pump.

And so off we went, and picked up where we left off, stopping at the very same petrol stations upon the very same road that we’d already driven along twice.

“No!” I protested to the driver. “Diesel nada.” But our bemused friend knew best. Pulling over beside the fifth petrol station to confer with a group of truckers, we were pointed down a little alleyway, where we soon arrived to the joyous sight of one particular trucker siphoning some Diesel from his tank into the jerry cans of another group of frustrated drivers – presumably for a princely sum.

Well, the price mattered little by that stage, and Bryn and I soon bought 45 litres’ worth (and eventually went back again for an extra 20), before heading back to the hotel to fill up the tank and set off to Samarqand – home to some of the most impressive Muslim architecture that I have ever seen.

Quite what we’ll do about the Diesel shortage in a few days’ time, I do not know. Perhaps Samarqand will be different, but that seems unlikely, given that there was none in the capital. For the moment, we will just sit back, relax, and enjoy our new surroundings in the enchanted city of Samarqand.

Sophie Ibbotson:

In my mind, Samarkand and Kashgar are the two great Silk Road cities. I went to Kashgar in 2008 and was sorely disappointed by the way the Chinese had flattened the city, consciously burying thousands of years of world history under strip malls, neon signs and mile after mile of concrete. It was therefore with some trepidation that I approached Samarkhand, not knowing if UNESCO had been able to hold back the ravages of time, cultural imperialism, and a chronic lack of taste.

The outskirts of Samarkand are not too promising. I bit my lip and kept my fingers crossed. As we came around the ring road, skirting fairly characterless blocks of flats and administrative buildings, the Registan popped into view across the rooftops. I let out a sigh of relief.

The origins of Samarkhand date back some 3000

years, but the most ancient parts were destroyed by Genghis Khan. The buildings we see today were built by his descendants between the 14th and 17th centuries AD. The so-called Timurid dynasty ruled an empire that stretched from Ankara to Delhi. Samarkand was their capital and, as such, a centre of patronage that drew the finest architects and artisans of the day. The superior quality of their work is clear in every dome, tile and tower.

years, but the most ancient parts were destroyed by Genghis Khan. The buildings we see today were built by his descendants between the 14th and 17th centuries AD. The so-called Timurid dynasty ruled an empire that stretched from Ankara to Delhi. Samarkand was their capital and, as such, a centre of patronage that drew the finest architects and artisans of the day. The superior quality of their work is clear in every dome, tile and tower.We stayed in a guesthouse a stone’s throw away from the Guri Amir mausoleum (the tomb of Amir Timur, sometimes known as Tamerlaine). The house was built in a traditional style around a courtyard, with fruit trees to offer shade. From the bedroom door we could reach out and pluck fat, juicy cherries to eat. At breakfast, served at a communal table in a second white-washed courtyard, we devoured fresh bread, homemade mulberry and rose petal jams, pastries, potato cakes and crepes. It was a perfect start to each day.

Quite understandably, it is the Registan that attracts the most attention in Samarkand. This exquisite collection of mosques and madrassas (Islamic schools) is arranged dramatically on three sides of a square, with the archways of the principal buildings rising up imposingly. Although the buildings themselves are brick-built, every inch of their facades are richly tiled. The majority of the tile work features the geometric patterns typical on Islamic buildings, but there is one notable exception: there are two orange tigers staring down at you from the corner panels of the archway to the right.

My favourite discovery, however, is far less frequented. On the furthest edge of the city’s graveyard, having disturbed a few sleepy marmots and an occasional snake, we discovered a row of domed tombs, the earliest of which dates from the 1300s. The place is quiet – there wasn’t another tourist in sight – and so, as we walked, it felt timeless. The tiles were a combination of a deep royal blue and shades of turquoise, all with an immaculate sheen that caught the evening light. A solitary figure, possibly an Imam, appeared briefly, paused to look along the length of the paved avenue between the tombs, and then disappeared as suddenly as he had come. The last of the day’s light faded and we wandered home entranced.

My favourite discovery, however, is far less frequented. On the furthest edge of the city’s graveyard, having disturbed a few sleepy marmots and an occasional snake, we discovered a row of domed tombs, the earliest of which dates from the 1300s. The place is quiet – there wasn’t another tourist in sight – and so, as we walked, it felt timeless. The tiles were a combination of a deep royal blue and shades of turquoise, all with an immaculate sheen that caught the evening light. A solitary figure, possibly an Imam, appeared briefly, paused to look along the length of the paved avenue between the tombs, and then disappeared as suddenly as he had come. The last of the day’s light faded and we wandered home entranced.

No comments:

Post a Comment